Factoring the Luhn algorithm

I work a lot in the field of e-commerce, and have written at least two shopping carts. Anyone who has implemented any kind of payment processing probably knows about the Luhn algorithm, which is a simple test that one can apply to a credit card number to make sure that the customer entered it correctly.

Factor and, I believe, concatenative languages as a whole can be very expressive when it comes to describing and implementing an algorithm. Let’s explore this.

Meet the Luhn

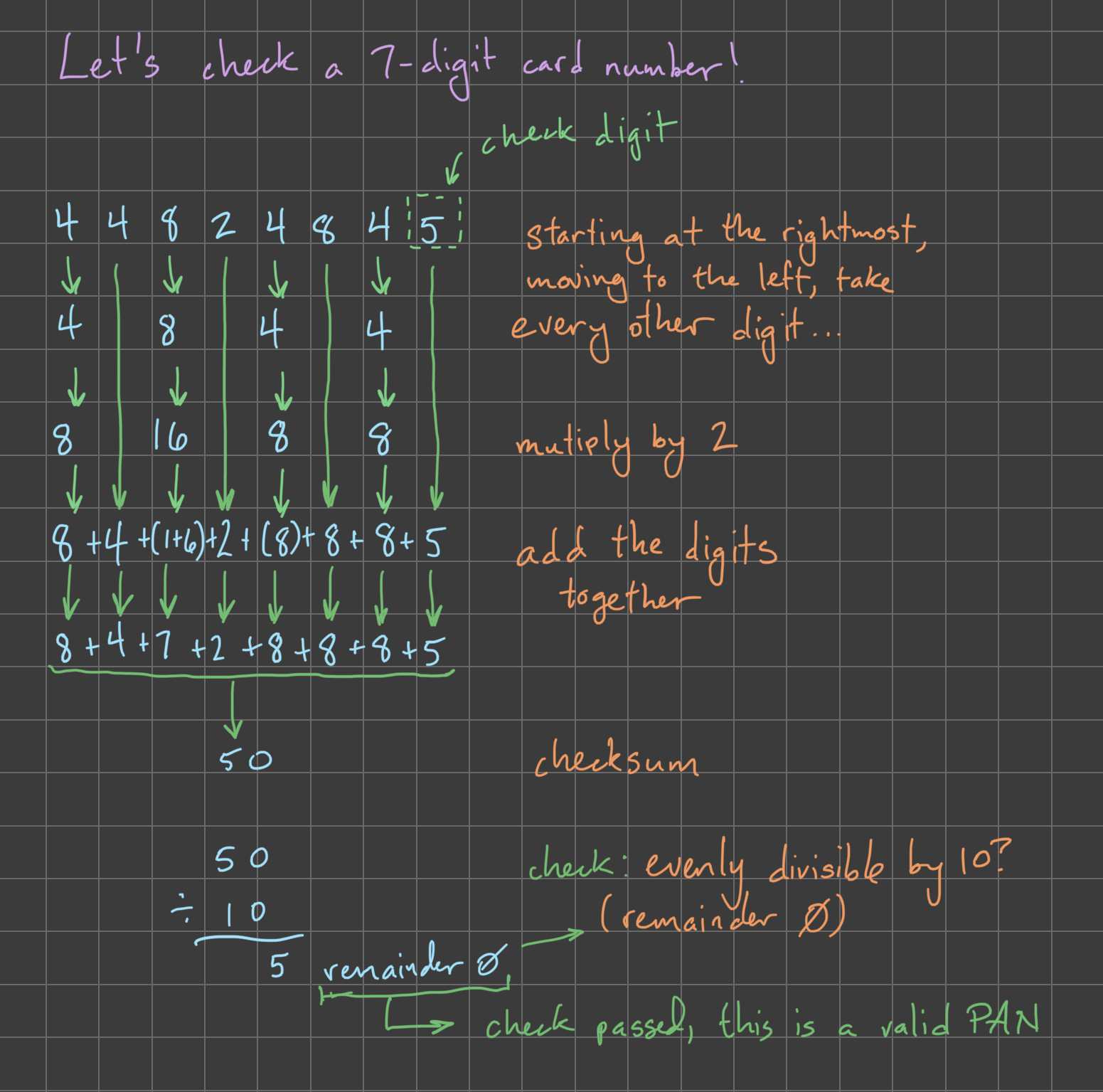

First, let’s look at an informal explanation of the algorithm

The formula verifies a number against its included check digit, which is usually appended to a partial account number to generate the full account number. This account number must pass the following test:

- Counting from the check digit, which is the rightmost, and moving left, double the value of every second digit.

- Sum the digits of the products (eg,

10 => (1 + 0) => 1,14 => (1 + 4) => 5) together with the undoubled digits from the original number.- If the total modulo 10 is equal to 0 (if the total ends in zero) then the number is valid according to the Luhn formula; else it is not valid.

Illustrated 7-digit check

The first whack

: luhn-check ( number-seq — passes? )

reverse #! Moving from right to left,

double-every-other #! double every other digit.

sum-digits #! Add the digits of the sequence, then

multiple-of-ten? ; #! test that the result is evenly divisible by 10.

The Factor description of the algorithm looks like a close approximation to the English description of the same. Interestingly, if you enter that word definition into Factor’s listener (i.e. REPL), Factor will note that double-every-other, sum-digits, and multiple-of-ten? are unknown words, however, you can “defer” the definition of those words and Factor will accept the definition. Pause for a moment here: Factor accepts without question words that it can’t actually evaluate or run which lets me start with this simple top-level definition and “fill in the blanks” as I go.

Craft the parts.

First, we need a word to double every other value in a sequence. That is, given the sequence { 1 2 3 4 5 6 }, we should get the result { 1 4 3 8 5 12 }.

Well, Factor supports a number of Lisp-like sequence combinators so this should be simple:

: double-every-other ( seq — seq-doubled )

[ odd? [ 2 * ] when ] map-index ;

For those new to Factor, [ … ] or “quotation” is the equivalent of (lambda … …) or function (…) {…} in your language of choice; that is, it defines an anonymous function. (For those who care about such linguistic details, “scope” or lexical bindings are an optional feature in Factor, in the locals vocab). Since Factor is concatenative, parameter passing is implicit and we don’t have to name or count the quotation’s arguments — Factor will infer them at compile time and warn if the program doesn’t add up.

Whereas map calls the quotation with each element of a sequence, map-index passes both the element and its index into the quotation: perfect for modifying every other index with the odd? predicate.

It’s almost readable as English: “Given a sequence, produce a new sequence, as so: if an element is at an odd index in the original sequence then double that element in the new sequence.” Yes, it sounds a bit stilted when read aloud, but it concisely and accurately confers the idea to the listener.

A few quick tests in the listener shows that this word works as expected.

Next we need a word that sums the digits of a sequence. That is, for the sequence { 1 11 5 }, this word should produce the sum (1 + (1 + 1) + 5) = 8.

Well, the sum word in Factor adds the numbers in a sequence together, but we need to treat two-digit numbers specially. Using integer arithmetic, the way to sum the digits of a two-digit number is to divide the number by 10 (num / 10) and add the remainder (num mod 10). Handily, Factor provides a /mod (read “divmod”) word which does both in one step. Let’s have a go at sum-digits:

: sum-digits ( seq — sum )

[ 10 /mod + ] map sum ;

Nothing surprising there. “Produce a new sequence as so: for each element of the sequence, apply /mod word to get the quotient and remainder, then add them together, placing the result in the new sequence. Sum the numbers in the new sequence.” Again, stilted, but readable.

On to the last word: multiple-of-ten?. This is simple, test if a number is evenly divisible by 10 — that is, the remainder of dividing the number by 10 is 0, or more simply: num mod 10 == 0.

: multiple-of-ten? ( n — ? )

10 mod 0 = ;

Very small, and easy to visually inspect and test.

Now we’re cooking with Luhn!

Well, that’s actually all there is to write; we’ve implemented all the parts the Luhn algorithm. The astounding thing is that we started with a simple definition and implemented the entire algorithm without changing the original definition!

A thought experiment

Imagine, as a Python or C++ programmer, if someone handed you a definition of a function and said “this definition can’t be changed, now implement all of the functions it calls.” In order to meet their original syntactic definition, I’d be hard-pressed and restricted in the features that I could use to implement the solution. If they used classes and OO-style code, I’d be stuck with the hierarchy they implied or I’d need to start hacking around them with templating, macros, monkey patching, or other such self abuse. Even if they didn’t use those features of the language, I’d be bound by the function calls and parameter passing in the original definition, which might make my life very difficult as I wrangle the data flow to produce their intended result.

Whereas, in Factor or Forth, handing a well-crafted but fixed definition of a word to someone can lead to an elegant solution that not only looks correct but runs correctly.

Don’t let me be misunderstood

Truthfully, I re-factored the words in this example several times (see the my commit history) before coming to this tidy little definition. I think it has to be experienced to be understood — rearranging words and testing them in an interactive environment feels natural and simply right. To paraphrase Chuck Moore, author of the Forth language, (speaking of implementing a Bluetooth stack), “first you have to figure out what they’re actually doing [in the algorithm], then you simplify the definition and fill in the parts.”

There is some ineffable “ah hah!” moment that comes when writing a well-factored program which makes me smile inside, some intangible correctness of having a readable definition that not only looks right but is right.

Look at the examples and tell me that a single one of those is more clear than this:

: luhn-check ( number-seq — passes? )

reverse #! Moving from right to left,

double-every-other #! double every other digit.

sum-digits #! Add the digits of the sequence, then

multiple-of-ten? ; #! test that the result is evenly divisible by 10.

Granted, those aren’t the most shining examples of implementations (hell, I’ve written stuff equally confusing), that this is a trivial algorithm, and maybe I’m getting old, but nowadays all of those just look like esoteric nonsense. (Really, look at the Java and Python implementations; way too clever for their own good).

Now if only I could grow a decent beard to go with these suspenders…

The source to this post is available on GitHub